Episode 39: One Man's Dream.

Ragweed... You bitch!

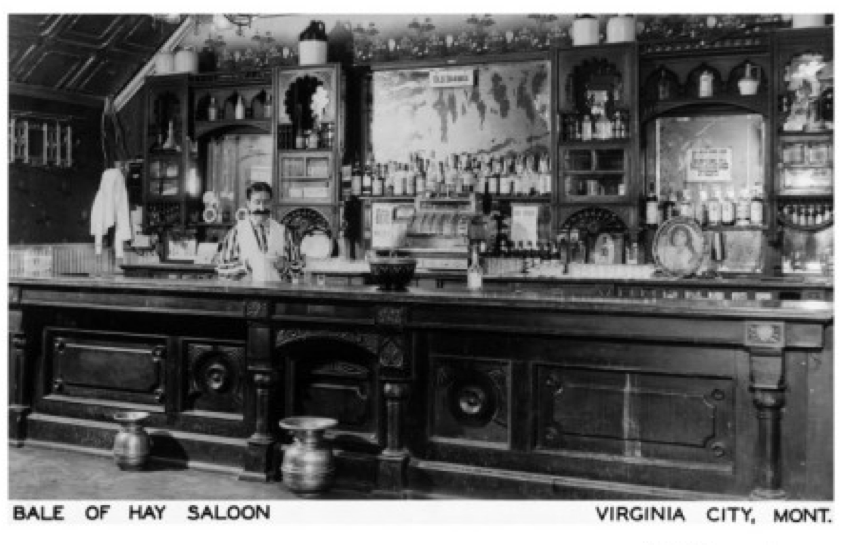

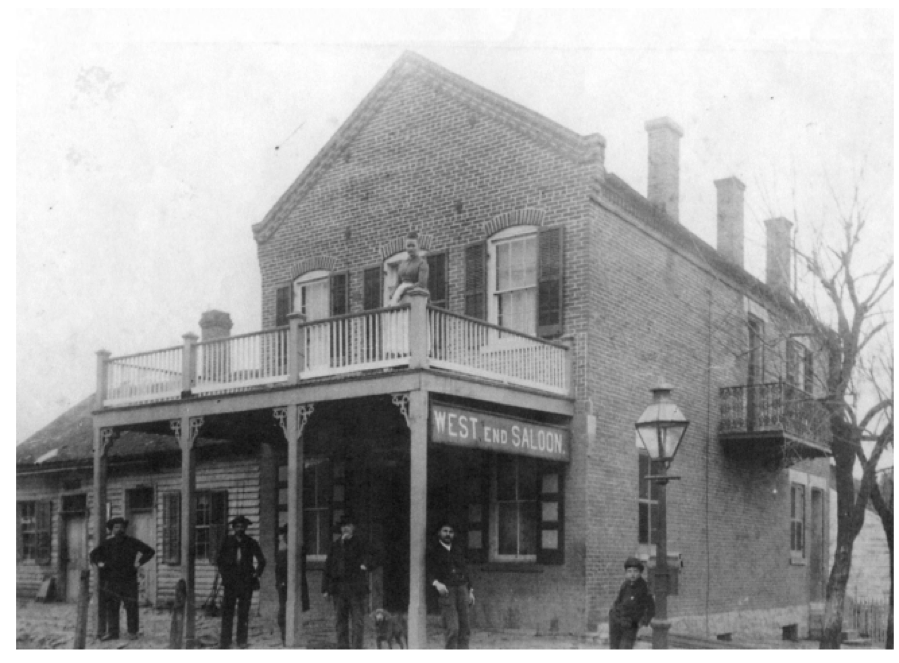

Soooo... Allen is feeling the brunt of the ragweed invasion and we've decided to give you an encore presentation of "TAVERNS, SALOONS, & PUBS: 10 OF THE OLDEST BARS WEST OF THE MISSISSIPPI." If you haven't heard it you'll definitely want to give it a listen and if you have heard it, ahhh it's been a few months, you may want to give it another go.

Enjoy and talk to you soon, - BMAC

Episode 38: America's Beer: Only in America.

What’s the connection between a 15th Century Italian Explorer, a 19th Bavarian brew master, a Bohemian Czech community, and Lite Beer from Miller? One last look at the “collisions of perfect storms” that made German style Lagers into America’s beer, plus Drunk Uncle Al’s Joke of the Week.

https://soundcloud.com/hishtory/americas-beer-only-in-america

Episode 37: America’s Beer: Beginnings of the Beer Barons

There’s been something burning Allen’s ass… and he let’s you know what. He revisits an earlier episode and a truly piece of FAKE NEWS, and blows up a pile of bullshit about the history of beer that’s been floating around on the interwebs for the past 21 years.

Also, a brief look a the climate surrounding immigration between 1840 and 1860, the German architects of the brewing industry in 19th Century America, and why American beer is “slightly” different than the German lager it’s modeled after. Along with a few words of opinion and Drunk Uncle Al’s Joke of the Week.

Episode 36: “America’s Beer.”

How did a country that was established by rebellious Ale drinking British subjects become a German Light Lager loving country? It’s an interesting story and goes back to mid 19th Century immigrants from Germany who brought their unique brewing practices to the United States. But, what’s the difference between Ales and Lagers? And why did the Germans, Bohemians, and Czechs brew lagers when all of the other cultures around them were brewing ales?

This episode touches on all of these topics, plus a special offer for Hishtory’s Patreon Patrons on next year’s Grand Pub Crawl Tour of Ireland, and, of course, Drunk Uncle Al’s Joke of the Week.

Episode 34: "Brotherly Love- Monks and Beer in Medieval Europe.

This week Allen takes a look at the foundations between Catholic Monasticism and the brewing of beer, beginning with Saint Benedict’s call for monastic hospitality in the 6th Century CE, and following the course of the Benedictine monks, who then split and morphed into the Cistercians, who then split and morphed into the Trappists, who still carry on the tradition of Monastic Brewing today, along with a group of American Benedictines who have brewing Belgian style ales in Italy since 2012.

IN ANNOUNCEMENTS: a call for more 5 star reviews on iTunes; invitation to a Salute to Santa Fe Brewing at the Pub; get your reservations in for The Grand Irish Pub Crawl (and some Hishtory) Tour in June 2018; and whoever hit Allen’s Chevy Volt at the HyVee is a fucking asshole.

Also, we received an email about depressing subjects in Hishtory.

And of course, Drunk Uncle Al’s Joke of the Week.

Episode 19: WEIRD, WHACKED, and WTF?!?!?

Ttsongsul: Korean Poop Wine

HISHTORIC HANGOVER HELPERS

Surströmming: Swedish Fermented (Rotten Fish) from the Mad Chef.

Chicago and Prohibition

Chicago, the Second City, the City of Big Shoulders, Chi Town, the Midwest Metropolis. It’s a great city, and what a fantastic wealth of history, especially the history of brewing in Chicago. Chicago was established in 1833, the first large commercial brewery, J&W Crawford’s Brewing Company, opened in the burgeoning city just two years later. Prior to that, the taverns of the frontier settlement had brewed their own beer, and with varying degrees of quality. During the late 1830’s and 1840’s a number of breweries popped up, with most of them failing and shutting down, but in 1842 an Alsatian immigrant, Michael Diversey, bought a struggling brewery and turned in around. “The Chicago Brewery,” as Diversey called it, produced ales and porters, and dominated the beer industry in Chicago until it was destroyed in the great Chicago fire of 1871.

In the 1840’s, German and Irish immigrants began to arrive in Chicago, and with the Germans came the brewing of lager beer, the favored beer of Germany. Lager beer differed from the more familiar American ales of the time; it was brewed using a slower acting bottom fermenting yeast rather than the top fermenting ale yeast. For optimum quality and drinkability, lager needed to be stored in cool underground caverns or cellars of about 45 to 55 degrees while it fermented, taking about three months for lager beer to finish out, whereas ale yeast could be used to brew beer in much warmer temps 65 to 70 degrees, and ales would finish fermenting in as little as a week.

In 1847 two German immigrants, John Huck and John Schneider, opened the first lager brewery in Chicago, and thus began the transition from Chicago, and America for that matter, of being an Ale drinking culture to a lager drinking country. However, the lager brewers at the time weren’t met with open arms by the old school American population. Lager was seen as foreign and different, across the established communities of the day by the nativist element, and Chicago was no exception. But it was not only the lager beer, but how beer was drank by these new immigrants and incorporated into their culture.

Cartoon depicting anti immigrant sentiment against Irish and Germans in the mid 1800’s

Sundays were family days for both the Germans and the Irish, but especially the Germans. Groups of immigrants gathered at parks and open common areas with family members and drank lager beer while eating, singing, and playing of games. Sunday was their day. There was no such thing as the weekend in the 19th Century, a concept that doesn’t come along until labor reforms began to emerge in the 1920’s and 30’s. Men, women, and some children of the poorer immigrant communities, worked 12 hour days, six days a week, Monday through Saturday- the 40 hour work week was decades away. Thus, Sundays became their day to be with family and friends and enjoy a drink. The German saloons began to build beer gardens, and the Irish taverns converted backyards into areas where the immigrant families would gather on Sunday afternoons. By 1850 more than half of Chicago’s population of 28,269 were foreign born, with the Irish comprising 21% and the Germans 17% of Chicago’s total population.

The old stock American population of Chicago was for the most part fearful of the foreigners, especially the Catholic Germans and Irish. The old school Protestant Christian population saw Sunday celebrations by Catholics as disrespectful and heretical to their values. In 1855 the “No Nothings,” a political party largely formed as an anti immigrant and anti Catholic movement, campaigned and elected Levi Boone, the great nephew of the legendary Daniel Boone, to a one year term as mayor of the city of Chicago, with Boone carrying a slim majority with 53% of the vote. He was racist, pro slavery, anti Catholic, anti immigrant, and a temperance reformer. To quell the rise of the German and Irish population and their merry making on the Sabbath, one of his first acts as mayor was to ramrod an ordinance through the city council which raised the saloon licensing fee from $50 dollars per annum to $300. Secondly, he declared that the city was going to enforce the long overlooked Illinois State law that prohibited Sunday saloon and tavern openings and sale of alcohol. At the time there were 675 drinking establishments in Chicago, of which only 55 were owned by old stock nativist Americans. The Germans and the Irish perceived Boone’s stance as an open attack on their values and way of life, and most refused to abide by the law. When the day came for the ordinance to go into effect, Mayor Levi Boone was ready.

Thirty three violators who had not paid the $500 for their saloon licenses were arbitrarily arrested, all of which were either German or Irish; not one nativist American was targeted, even though it was known that some of them had not paid the new license fee. It was agreed by the prosecution and defense attorneys that only one of the defendants would be tried, and that trial would be used as a test case for the rest, and whatever the outcome of that one case, the same verdict would be applied to all. On the court date, only a few of the immigrant saloon owners and their patrons showed up at the courthouse to see the outcome of the trial, but the judge presiding over the case had been delayed in getting to Chicago, and the trial was postponed to begin the following day. This gave the saloon owners and their followers time to pull together a mob of protestors, numbering more than 600, and the next morning they marched upon the courthouse, clubs, guns, knives, and bricks in hand, and clashed with over 200 policemen and deputized citizens. Shots rang out; a policeman was so severely wounded by a shotgun blast that he had to have his arm amputated. One of the protestors was shot in the back, and died three days later. Most of the fighting was hand to hand, repeating firearms were still a new thing at the time and were owned by very few persons. The local militia arrived with cannons, which the bared down upon the rioters and warned of opening fire. The leaders of the protest called their followers to back down and they returned to their neighborhoods. So ended The 1855 Lager Beer Riot of Chicago.

Levi Boone, Mayor of Chicago 1855-1856

Eighteen rioters were arrested; sixteen Germans and two Irishmen. Only the two Irishmen were brought to trial, the charges against the Germans were dropped. Both of the Irishmen were found guilty of creating a public disturbance, but on their appeal, the charges were thrown out. The city council, worried about another immigrant riot, rescinded Boone’s increase in license fees and agreed to return to the practice of overlooking the State of Illinois’ Sunday Saloon closing law. Boone, seeing that he had no chance of winning reelection, did not run for mayor in 1856. The riot did have one outcome; for the next150 years, the immigrant population of Chicago, along with their children and grandchildren, coalesced to form one of the most critical voting blocks in the city, whether it was Republican in the 1800’s and early 1900’s, or Democrats after the 1930’s.

For us looking back at Prohibition in 1920, from our vantage point of nearly one hundred years later, we can easily wonder what the public was thinking. One only has to look at the Lager Beer Riot incident in 1855 to see what happens when you try to impose a law upon people who believe that it is unjust. This wasn’t just an attack upon drinking; this was a law levied against a way of life. And by 1920 when the 18th Amendment went into effect, it’s mind-boggling to believe that the proponents really thought they could stop drinking in America? It was insane. Society was primarily comprised of European cultures. One simply has to look at the history of the Greeks, then Romans, French, Germans, the Scots, the Irish, the English, the Norse, the Slavic countries- these are all drinking cultures and the interwoven place of alcohol within these societies is without question, and for a few thousand do-gooders in the early 1900’s to think that they were going to be able to stop the drinking habits of 100 million people in America is ludicrous. People are going to drink, and someone was going to make certain that they would be able to do such. When we look at the drug cartels today, who are in the business of smuggling and selling contraband through a black market, with violence always as a tool of their trade, well it’s not surprising to us when we look back upon what happened.

Advocates for the Temperance movement, late 1800’s. My response to their slogan, “Good!”

The late 1800’s and the very early 1900’s saw was the rise of the Anti Saloon Leagues and the Temperance Societies in America. Their goal was to curb, if not completely eliminate the consumption of alcohol in the United States. And how they were able to politically make this happen is a convoluted and crazy chapter in American history. It was believed by many of the reformers that all of the social ills in the United States- poverty, unemployment, spousal abuse, child abuse, chronic illness and disease, crime - were in part or wholly a result of the consumption of alcohol. And while these things may be associated with alcohol abuse in certain individuals, alcohol itself was not the cause of abuse and degradation in society.

The first salvo in the dry versus wet war came in October of 1918, near the end of World War I, when Congress passed the Wartime Prohibition Act, which banned the sale of any alcoholic beverages that were more than 2.75% alcohol by volume. The so called rational behind the law, was that it would save grain during the war, but it was actually an attempt at appeasement towards the Temperance and anti-saloon movements. President Wilson didn’t sign the law into effect until November 11, 1918, which was the day that War actually ended and the law did not go into effect July 1st of 1919. The result of this first attempt at prohibition was that breweries began making lower alcohol beers, and distillers around the country slowed down production until it was known how long the law would remain.

But, before the Wartime Prohibition Act could go into effect, our brilliant political leaders ratified perhaps one of the most short sighted changes ever to the US Constitution. January 16, 1919, the 18th Amendment to the Constitution was passed by the required measure of 36 state legislatures. President Woodrow Wilson vetoed the bill when it came to his desk on October 27, but his action was overridden the very same day by that brilliant ship of fools known as the US House of Representatives, and the next day, the Volstead Act, named after the chairman of the Congressional Judiciary Committee, US Congressman Andrew Volstead of Minnesota was ratified into law, to go into effect on January 17th, 1920. The long title of the act was: “An Act to prohibit intoxicating beverages, and to regulate the manufacture, production, use, and sale of high-proof spirits for other than beverage purposes, and to ensure an ample supply of alcohol and promote its use in scientific research and in the development of fuel, dye, and other lawful industries.” The law superseded any and all state prohibition laws already in effect, and made it illegal to manufacture, transport, and sell intoxicating liquor. What the law didn’t make illegal was the consumption of said liquor.

Six months before Prohibition went into effect, Chicago had 43 breweries in the city, but only 16 renewed their brewing licenses to make full strength beer for 1920. These few breweries held out hope that the politicians would come to their senses and abolish the law and that they could get back to business. Some of the brewers applied for near beer brewing licenses, what were being called “cereal beverages.” Of the over 7,000 dram shops in the city, very few bothered to renew their liquor licenses for 1920. On the Loop alone in downtown Chicago, there were 120 bars, of which only 16 renewed their licenses in hopes of a miracle. And the saloons, bars and taverns at the time were more than just drinking establishments; they neighborhood centers, where news was traded, or employers went looking for workers, and where at time when there was a distrust of banks, it was where the working class could get their paychecks cashed. The business owners were slowing watching their livelihoods disappear, vanish, and they had no idea what they were going to do. It wasn’t long before Chicago soon ran out of real beer, even before prohibition went into effect, and saloon keepers were forced to sell soda and cereal beverages. The brewers and business owners of the city appealed to both Springfield and Washington DC, citing that besides the thousands of jobs that were going to be lost- brewers, maltsters, warehouse men, coopers, teamsters, truck drivers, salesmen, bartenders- they estimated that the city was going to lose 8 millions dollars in tax revenue, and much more than that in real wages and . To which the Dry proponents glibly responded, a minor increase in local taxes would easily cover the shortfall.

The 18th Amendment went into effect at midnight on January 17th, 1920. And the first documented violation of the law happened, according to police reports at 12:59 AM in, guess where, Chicago. Six armed men broke into a two locked railroad cars and stole $100,000 worth of “medicinal” whiskey. It was the first of thousands of organized crime activities in the Windy City over the next 12 years.

There were many who just sat back and waited, quietly observing what was going on, the grumblings, the worrying, the frustration and disappointment at what was about to happen. These people realized that prohibition wasn’t going to fly with the people of Chicago, a population who was accustomed to serious libations. And one of the observers was a local pimp and racketeer, Johnny Torrio.

Before Prohibition, organized crime in America… wasn’t. Local gangs controlled the prostitution and gambling rackets, and there were turf wars, but nothing like what America was going to see over the next 80 years, and Prohibition was catalyst for the rise of organized in the United.

In Spring of 1919, seeing the writing on the wall, Johnny Torrio, along with brewer Joseph Stenson, started to buy up breweries in Chicago and the neighboring suburbs. Later there were other investors/gangsters/bootleger; Dion O’Banion, Hymie Weiss, and Maxie Eisner, to name a few, but Torrio was the brains behind the move. He arrived in Chicago from New York sometime around 1911, and he joined the Colisimo organization, controlled by Big Jim Colisimo, the boss, which ran the prostitutes and rackets on the south side of the city, under the political protection of First Ward Alderman Michael Kenna. It wasn’t long after Torrio’s arrival that Big Jim offered him the position as his right hand man.

Johnny Torrio (center) and henchman, circa early 1920’s

Torrio was not the typical gangster of the era. He was a quiet man, he seldom carried a gun, and he dressed like a mid level management businessman; nothing flashy or excessive, despite the fact that he had amassed a huge amount of illegally gained wealth. And although he was a pimp and by that occupation he rose in the Colisimo organization, he never slept with any of the prostitutes, nor did he drink or smoke. He was home every night by 6:00pm to be with his wife for dinner in their modest Michigan Avenue apartment. But, he had a great deal of business savvy, superb organizational skills, and was an outstanding negotiator who could handle the art of compromise. And these skills served him well as he and Stenson purchased, leased, of fronted the amassed Chicagoland breweries.

Torrio’s plan was genius. After gaining control of the breweries, they would put well-paid pawns in the position of brewery presidents and managers. John Stenson, the brains behind the breweries day to day operations, hand picked the people for the job. If and when the breweries were raided by law enforcement, the appointed brewery officers and managers would take the fall, be arrested, then would be bailed out by Torrio’s attorneys, and then the local bribed politicians would be paid off to make the charges go away. The brewery officers and managers, if they did their job well and took the fall, were handsomely awarded, and would in a matter of days be back at work in the brewery. And the way all of this was paid for was by a slush fund that Torrio held back on every barrel of beer. The syndicate was selling a barrel at $50 to $55 each, of which $10 was held back on each one. It is estimated that Torrio’s operation, by 1924, was generating between 28 and 51 million dollars a year in sales

When Prohibition became law in Chicago, Mayor William Thompson made sure that brewery raids were as uncommon as a snowball in hell, and local saloons openly operated, with thousands of licenses being issued for Soda Parlors, the most common front for bars, taverns, and saloons. Virtually every cop and politician in the city knew what was going on and they turned a blind eye, with their pockets stuffed with cash.

Torrio continued to consolidate his power across the city, bringing gangs together with everyone reaping the benefits of bootlegging. The north side, at Torrio’s direction, was run by Irish mobster, Dion O’Banion. The west side was ran by two buys named Druggan and Lake, while Torrio maintained direct control of the Southside, but where there is money, there is going to be competition, and it came in the name of Spike O’Donnell.

The O’Donnell gang was a small operation, in comparison to the Colisimo organization, but they were brash and had hijacked several truckloads of Torrio’s beer and took it out of town to sell. When Torrio failed to retaliate, out of fear that if violence erupted it would bring on the scrutiny of law enforcement, the O’Donnell’s continued to hijack trucks, and then had the balls to move into Torrio’s territory and through intimidation and violence, forced Torrio’s saloon accounts to buy the stolen beer. Torrio continued to turn his cheek, held his enforcers at bay, and to regain the saloon accounts, lowered the price of a barrel of beer by $10. But, eventually, somebody in the Torrio organization had had enough, and one of the O’Donnell’s beer runners name Jerry O’Connor was shot and killed. Accuse in the shooting was one Dan McFall, a known Torrio ally.

In April of 1923, William Dever was elected mayor of Chicago, mainly because the people of the city saw Big Bill Thompson getting very rich off of the illicit criminal activities associated with bootlegging and illegal brewing. And just as Johnny Torrio had feared, Dever used the O’Connor shooting as a catalyst to begin a crackdown on the scores of breweries that had been operating in Chicago with impunity. Dever held a press conference and announced his intent to close down the breweries, with each one shut down then being put under police guard so they could not be reopened, and police patrols would be increased so beer from neighboring communities could not be brought in by truck.

Torrio and the others got creative. The cops didn’t have enough manpower to guard every brewery in town, so at those facilities that they hadn’t yet shut down, trucks filled with near beer would drive out of the front doors, while sneaking out the back would be carefully disguised shipments of real beer. Another strategy employed was buying cops at the precinct headquarters so they would tell the bootleggers when and where the raids were coming. The cops kept shutting down saloons, however, and with that there became fewer and fewer places for the gangsters to sell their bootlegged beer. So when competition begins to get fierce between the gangs who had before hand been working, people start eliminating their competition, and that means killing.

Dever’s war on the gangsters backfired; instead reducing violence and murder, it escalated it. But Dever swore he wouldn’t back down until every brewery, every saloon, every soda parlor, every grocery store that sold liquor or beer was shut down. Besides that, Dever began a campaign of circulating “alternative facts” that the gangsters were poisoning their product, which makes no sense at all- why would you want to kill your customer base. But, there were people getting poisoned, they were buying product from less scrupulous sources to get alcohol; homemade bath tub gin, for example, which was often made with wood alcohol or methanol, both of which are toxic. Johnny Torrio may have been a gangster, but he wasn’t a crook; he never cheated his customers, his informants, his employees, or the cops and politicians he had on the books. Everybody down the line was taken care of, it was just good business.

Through 1923 and 1924, Dever continued his crusade to end drinking in Chicago, while Johnny Torrio and his associates and competitors continued their work in brewing beer and helping saloon owners keep their doors open. But Torrio had one major problem in his alliances; Dion O’Banion.

Dion (Dean) O’Banion

O’Banion was an Irish mobster on the city’s North Side, and besides being a bootlegger, he owned a florist’s shop. Of all of Torrio’s coalitions, O’Banion’s was probably the most fragile. O’Banion’s style was quite different Torrio’s; whereas Johnny would try to smooth over disagreements with competitors and try to come to a mutual agreement, Dion O’Banion was always ready to resort to violence. An example of the difference between Torrio and O’Banion’s styles of negotiation happened when two crooked, but enterprising, police officers held up one of O’Banion and Torrio’s beer trucks. As was customary, the drivers paid the cops $250, which was the going rate to let the bootleggers go on about their business, but the policemen demanded an additional $300. Then drivers, who didn’t have the authority to give over the extra cash, went to find a phone, while the cops watched the truck. They called O’Banion at his florist shop, where unbeknownst to the gangster, the police had the phone line tapped. When the driver told O’Banion the story, he screamed over the phone “Three hundred to them bums? I can get them knocked off for half of that!”

The drivers, being a pretty astute guys and knowing they might be in over their heads, called Torrio who gave them instructions. The drivers then called O’Banion back and relayed Torrio’s instructions; pay the cops, don’t let them have an excuse to cause trouble. The cops leaked the news of the incident to the press, and the Chicago Daily News rightfully reported, “It was the difference in temper that made Torrio all powerful and O’Banion just a superior sort of plug.”

In another incident, a small time gang by the name of the Genna family was selling homemade, substandard hooch in O’Banion’s territory. O’Banion demanded that Torrio send the Genna’s back into their own territory, but before Johnny’s associates could negotiate a deal with the Gennas, O’Banion sent his men to hijack a truckload of the Gennas cheaply made alcohol in retaliation, along with beating the driver to within an inch of his life. Only through Torrio’s skills of compromise was he able to stop the Genna family from retaliating and starting an all out gangland war on the Northside.

O’Banion was chaffing at being under the Torrio’s command, and he began to hatch a plan to put Torrio away. O’Banion announced that he was retiring from the bootlegging business and retiring to Colorado for the clean air. He offered to sell his shares of one of their co-owned breweries for half a million dollars. Torrio, along with one of his junior associates, Al Capone, who also had a stake in the brewery. Both men jumped at the deal, joyful to hear that the troublesome Irishman was leaving town. The three were to meet at the brewery on the early morning of May 19, 1924, for the final transaction and completion of the sale. What Torrio and Capone did not know is that O’Banion had been tipped off that a federal raid was going to come down on the brewery on that very morning. Because Torrio had a prior conviction for violating Prohibition laws, O’Banion hoped that his plan would lead to Torrio being arrested, because the boss would face a possible minimum of three years in a federal penitentiary, which would allow O’Banion, (who surprisingly had not one conviction on his record- his underlings always took the fall for him), with Torrio being put away, to make his move, and take full control of all Chicago bootlegging operations from Torrio and Capone.

On the early morning of May 19, 1924, at the former Siebens Brewery on Larabee Street, the largest manufacturing facility of illegal beer in the Chicagoland area, Southside crime boss Johnny Torrio and Northside gang leader Dion O’Banion, along with a cadre of thugs and enforcers, met to facilitate the transfer of O’Banion’s shares in the brewery to Torrio and Al Capone. As Torrio’s right hand man, Capone was going to be there for the deal, but the night before he and Torrio agreed that Capone didn’t really need to attend. However, a Chicago police and US Treasury Department cooperative raiding party did show up, and besides Torrio and O’Banion they found five trucks loaded with 150 barrels of beer, full mash tuns of fermenting wort, and a racking room full of barrels. O’Banion, in a feigned attempt to look like he was trying to flee, took a ledger book and not so subtly threw it under the loading dock so that the agents saw him do such. When one of the agents looked into the book he found recent dates of deliveries and quantities of beer to saloons, groceries, and other shops, along with a record of which Chicago police offers, politicians, and prohibition agents had been paid off to leave the brewery’s operations alone.

Seibens Brewery Building, North Larabee St., circa mid 1960’s

O’Banion was glib during the entire event, which peaked Torrio’s suspicions. Both men, along with thirty-one gang members, were arrested and taken to the Federal Building, where O’Banion almost managed to slip away, but he was caught before getting out of the building, to which he joked with the agents about being recaptured. Torrio had thought they would be taken to the district police station, where he would make a generous payment to “Widows and Orphans” fund (i.e. a bribe) and they would be released, but instead when they were taken to the Federal Building and charged with violations of Federal law he immediately smelled a rat. When it came time to make bail, Torrio peeled off $7,500 from a wad of bills, but dismissively left O’Banion to his own devices, who had to call a bail bondsman to front the five grand to secure the Irishman’s release.

The Sieben Brewery building, which Torrio, O’Banion, and Capone leased from the Sieben family, was operated by a patsy named George Frank, installed into the job by Torrio’s brewing partner, Joseph Stenson. On paper, Frank had no connection to the crime syndicate. Apparently, law enforcement had been watching the brewery for a long while, biding their time for the opportunity to catch the principals on the premises when they raided the brewery.

It didn’t take Torrio long to see through O’Banion’s ruse to get him out of the picture. He knew he would eventually get his revenge, but first he had bigger problems to take care of; with a federal indictment hanging over his head, he had to keep a low profile and turned the day-to-day operations over to the young 25 year old Al Capone.

Alphonse Gabriel Capone was born in Brooklyn New York in 1899, the son of Italian immigrants from Naples; his father was a barber and his mother a seamstress. Al was one of nine children, and ironically, one brother Vincenzo, had a career that strangely paralleled Al’s- he changed his name to Richard Hart, went to work for the Treasury Department and became a Prohibition agent in Nebraska. Two other brothers, Frank and Ralph, remained close to Al and worked with him throughout his criminal career. Al was initially a good student, intelligent and gregarious, but he developed behavior problems in adolescence and was expelled from school at age 14 for hitting his teacher in the face. As a teenager he worked at a bowling alley and ran errands for Johnny Torrio. Torrio grew to know Alphonse very well, and learned that he could trust the young man with the most sensitive of errands.

Frankie Yale

Al jumped around from gang to gang, just small time stuff, until joining the very powerful Five Points Gang. There he worked for and was mentored by racketeer and hitman, Frankie Yale, who tended bar in Coney Island at a saloon called the Harvard Inn. It was there that Capone got into a fight with another gang member over Capone insulting a woman. In the fight, Capone was nastily cut on the left side of his face, earning him the nickname of “Scarface,” which he hated. In 1919, Capone was involved in a fight with a member of the notorious White Hand Gang, an Irish gang that worked the waterfronts of Manhattan and Brooklyn. Capone nearly killed the Irishman, and the word on the street was that the White Hands had put out a contract on a “scarfaced dago.” At the urging of Yale, Capone left New York for Chicago and began to work for Torrio. Capone would eventually be involved in the extermination of the White Hand Gang. Beginning 1925, with the cooperation and permission of the mafia in New York, Capone is suspected of putting out contracts on all of the lead figures of the White Hand Gang. By 1928 the White Hands were gone and the Italians ran the docks of New York from that point on.

Upon his arrival in Chicago, Capone was immediately hired by Torrio as an enforcer at one of his brothels. Capone, although married with a son, couldn’t keep from sampling the goods, and soon contracted syphilis from one of the prostitutes. He probably would have had a successful recovery from the venereal disease had he gone to a doctor and taken Salvarsen treatments, but he didn’t want Torrio to know that he had been fucking the help, and as a result, syphilitic dementia would disable Capone over the last decade of his life.

The year following Capone’s arrival in Chicago, Prohibition was enacted, and Torrio and his boss, Big Jim Colisimo, had a disagreement over business. Torrio was ready to move into the bootlegging game, and had already purchased or leased a number of breweries, but Colisimo was worried that it would bring on heat from federal law enforcement that would interfere with the existing, and profitable, gambling and prostitution rackets. Torrio saw Colisimo as an impediment to income growth, and invited Frankie Yale to Chicago to do a job for him. On May 11, 1920, Colisimo was shot dead in the main foyer of the café he owned. No one was ever brought up on charges, although rumors had it that Yale and Capone had carried out the hit. Torrio stepped in and took over complete control of the Colisimo organization.

Assassination of Big Jim Colosimo

Between 1920 and 1924, Al Capone was not a publicly known name, but he quickly became Torrio’s most important henchmen; he stepped in and took over more and more of Torrio’s Southside and Cicero operations, allowing Torrio to concentrate on expanding the business, acquire more breweries, work on resolving disputes between the small gangs all across Chicago so that the flow of beer and whiskey could continue and bootlegging could be profitable for everyone. But then Dion O’Banion thought he could do better without Torrio in the picture, which led to the raid on the Sieben Brewery.

The Sieben Brewery was Torrio’s largest producing facility, and the loss of it hit the syndicate hard. Having seized the ledger with all of the syndicate’s warehouses, breweries, and customers listed, the Feds and the cops under Mayor Dever’s direction were able to tighten the noose on the bootlegging activities of Torrio’s operations, which had a crippling effect on income generation. The whole enterprise relied on lots of cash; to pay off cops and politicians, to buy materials for production, to maintain equipment, to pay workers. Nobody would work or sell materials on credit given the volatile circumstances at the time, nor was anyone going to write a check that could later be used in court as evidence, even though no one in the racket had a bank account in their name.

With the shortage of production, beer prices rose from $55 dollars to $100 per barrel. And the syndicate started losing market to a new innovation: Needle Beer. So, here’s how needle beer worked- There were five legally operating breweries in Chicago, all of them making near beer of less than .05% alcohol. The saloons and soda parlors would by have barrels of legal near beer delivered to their establishments at $35 per barrel, with the legal Federal Governement Revenue Stamp upon them, then the shop owners would then take a needle and large syringe, insert the needle into the bunghole of the barrels and pull out a particular measure of near beer, then displace that amount with moonshine, grain alcohol, or whiskey. Different bars used different methods, some even displaced the near beer with ginger ale and grain alcohol, giving the needle beer a much enjoyed sweeter profile. The only income that the syndicate and gangs were seeing off of this practice was the purchase of whatever alcohol was being bought from them.

Meanwhile, that summer, O’Banion and his wife did go to Colorado- as he told Torrio he was going to do, but he had no intention of retiring there. His gang was still following his orders back on the North Side, with O’Banion returning to Chicago in the fall of 1924. On the evening of November 9th, at his florists shop, O’Banion received a phone call placing a large order for a floral arrangement for a funeral that would be picked up the next morning. Three men arrived at O’Banion’s shop that next morning, O’Banion greeted them cordially, one of the men, Frankie Yale, extended his hand and grasped O’Banion’s in a hand shake, which he gripped very tightly, while the other two men, members of Genna family, pulled pistols from beneath their jackets and fired four shots into O’Banion- two into his chest, two into his throat. O’Banion fell to the floor, still conscience, and Yale then pulled out his pistol finished him off with a shot to the back of the his head. There was one witness to the murder, an O’Banion shop employee who saw the whole thing, but when the police arrived he said he didn’t know who the men were, and couldn’t really describe them very well.

A few weeks later, on January 25th, 1925, while still out on bail waiting for his trial of federal bootlegging charges, Johnny Torrio and his wife returned to their apartment after a day of shopping when two members of O’Banion’s gang, Hymie Weiss and Bugs Moran, pulled up in a car, shot Torrio’s chauffeur, then turned and fired at Torrio, hitting him in the chest and neck. Moran then stood over Torrio and fired a shot into his groin and arm, then pressed the barrel of his revolver and pulled the trigger, but the chamber was empty. Their guns empty, and a large crowd gathering, the two assassins panicked and fled, leaving Torrio severally wounded, but alive. At Jackson Park Hospital, Al Capone slept on a cot in Torrio’s room, armed and ready in case of another assassination attempt, all the while his mentor was recovering. Only two weeks earlier, Capone himself escaped an attempt on his life by Weiss and Moran; with the attempt on Torrio’s life, Capone knew that it was either us or them.

While convalescing in the hospital, Torrio realized that his coalition of pimps, racketeers, bootleggers, murderers, and extortionists had fallen apart. A month after the shooting, only a few days after having been released from the hospital, Torrio appeared in court to face federal charges. Still bandaged and weak from his wounds, he pled guilty, was sentenced to $5,000 fine and nine months in Lake County jail. While in jail, Torrio called for Capone. Johnny knew that he was probably still a marked man, and a third conviction on federal charges would mean he probably would never see the outside of a prison for the rest of his life. He told Capone he was handing over the reigns of his organization to do with as he pleased. After his jail sentence was over, Torrio and his wife moved to Italy in late 1925 and stayed there for 3 years before coming back to a life of retirement in New York. He became involved in some legitimate businesses, including a legal liquor distributorship which he owned along with Dutch Schultz, but he ran afoul with the IRS and plead guilty to tax evasion in 1939 and spent another three years in jail. Afterward, he lived peacefully, splitting his time between Brooklyn and St. Petersburg, Florida, until 1957, and while waiting for a haircut in a barber’s chair in Brooklyn, he suffered a massive heart attack, and died in hospital a few hours later.

When Capone took over the organization he already had plans and was ready to move. First things he did was set up two networks for getting whiskey into Chicago- Canadian whiskey by boat from Ontario, and Scotch whisky by truck from Nucky Johnson, the political boss of Atlantic City. The other thing he concentrated on was a way to get back into brewing beer. With the Treasury departments attention fully upon all of the major shutdown breweries, there was no way that he was going to be able to get them up a going again, so he started a number of smaller clandestine brewing operations in warehouses in deserted and little used industrial areas throughout the city and suburbs, what some have referred to as “wildcat” breweries. And he had help in this endeavor in the form of a very famous, but most unlikely, associate.

Some of Capone’s men had been sent to St. Louis to steal barrel-tapping devices known as golden gates from the Anheuser Busch Brewery. When August A. Busch learned of the theft and who had done it, he sent his son, Gussie –yes, the same Gussie Busch who bought the St. Louis Cardinals in the 1950’s and led the franchise to success over the following four decades- to Miami to talk to Capone, who was in Florida on extended vacation. During the meeting, the two ultimately reached a deal that provided Capone’s wildcat breweries with over two hundred thousand of the tapping devices, but ALSO with yeast, sugar, and malt extract syrup for his wildcat brewing operations. This made the brewing of batches of beer so much faster; by using malt extract syrup, Capone’s operations were able to bypass the lengthy and bulky method of mashing the malted barley and extracting the sugars needed for fermentation, a process that could take a day at least. With the malt extract syrup, all that had to be done is boil water, add the syrup and hop pellets, mix, let it cool, add the yeast and within a week you had beer ready to be barreled and sent to the saloons.

L to R: Adolphus Busch III, August A. Busch, and “Gussie” Busch, preparing to deliver the first legal beer to Washington DC after the repeal of Prohibition.

Gussie asked Capone to sign a contract on the deal, but the gangster laughed, told naïve Busch that a handshake would have to do. Over the lean years of Prohibition, Capone made a small fortune for Anheuser Busch by buying equipment and supplies from them. In his younger years, perhaps because he felt like it gave him a certain cachet, Gussie Busch would often tell friends of his meeting with Capone, but as he grew older and wiser he avoided the subject. I doubt they talk about that on the official tour in St. Louis.

While this new arrangement and the wildcat breweries had taken some of the pressure off of Capone and his organization in 1926, he still had to deal with troublesome North Side remnants of O’Banion’s gang. Capone offered peace if Hymie Weiss and Bugs Moran would come into business with him, a successful technique he hand learned from Torrio. Capone offered Weiss all of the beer concessions north of Madison Street if he allowed the rest to Capone. Weiss refused unless Capone handed over O’Banion’s assassins, including Capone’s friend Frankie Yale. Capone told Weiss that was just something he could not do, and knowing that Weiss would again try to come after him, Capone put a contract out on Weiss, and that contract was fulfilled when Weiss and two of his men where mowed down by machine guns in October of 1926. By the way, many people when you hear the name Hymie Weiss immediately think that he was Jewish, but he wasn’t- he was Polish Catholic, his birth name was Henry Earl Wojciechowski, and was buried Chicago’s Mount Carmel Cemetery, where his mentor, Dion O’Banion was also buried.

Hymie Weiss

With Weiss out of the way, Capone called for a citywide peace conference with the remaining rival gang leaders. At the summit Capone called for unity, offering to share the lucrative beer market with his former adversaries. “There’s plenty of beer business for everybody,” he said, “why kill each other over it?” A pact was reached; Capone kept all of the business in South Chicago and in the West including Cicero. The rest of the city and suburbs were divided among the others, and any and all disputes thereafter would be subject to arbitration through Capone himself. So, with there no longer needing to be any violence between the gangs, the bootleggers turned to securing more beer accounts.

The beer drummers, that is the salesmen, approach to marketing the product was simple; buy our beer or else. Intimidation and physical violence proved to be effective motivators. The days of needle beer were over. If motivating the saloon keeper to buy the product proved unfruitful, then a well placed pipe bomb overnight would usually close the deal. Arriving the next morning to their shop, one of Capone’s sales agents would show up, “Geez, if you had been selling Ace Beer, I bet that wouldn’t have happened.” With a shop owner having the front of his saloon blown open, and having no way to fix it, Capone and his associated gangs would agree to fix the mess as long as the saloon keeper agreed to sell their beer and no other. And the saloon keeper had to do what Capone’s men told him to do, or the next bomb wouldn’t blow up in the middle of the night when no one was there.

In 1927, there was another great development for the bootleggers; William “Big Bill” Thompson, who had been mayor when Prohibition started, was back in office having won the mayoral election over Prohibition crusading William Dever. Capone backed Thompson’s campaign heavily, and he won the vote with 515,716 votes to Dever’s 432,678. Dever had lost the support of his own Democratic party, many of the leaders of which had seen that his heavy handedness in dealing with the bootleggers had brought on more violence, not less. Capone went to work with alacrity; he muscled in on and took over the territories of smaller gangs, like the Saltis and O’Donnell’s, giving them a chance to go along but if not…

In 1928, with a staff of 300 plus agents, the Chicago unit of the Prohibition Bureau was joined by a young ambitious agent named Eliot Ness. Ordered by the US Attorney to start in the Chicago Heights suburb, Ness had success in busting a number of gambling and bootlegging operations, and on that strength he was assigned to start working on Cicero and the Southside of Chicago. To find out where the beer was being brewed, Ness assigned agents to watch saloons and restaurants and wait for trucks to pick up empty beer barrels. But, Capone and his associates had a strategy; barrels would not be taken to the breweries but to warehouses where they would be cleaned. They continued the strategy but were unable to determine where the beer was being brewed. And this is not surprising, as Capone would mover these portable wildcat breweries quite frequently, breaking down equipment and moving under cover of darkness to a new location.

Eliot Ness

Eventually Ness and his men were able to track down some empty barrels to a warehouse on South Lumber Street that they were certain was a brewery and the rushed in busting down the front doors of the building, only to find a set of steel doors, which took them a number of minutes to open and by the time they did, everyone inside was gone. Inside they found nineteen 1,500 gallon vats, two new trucks, and 140 barrels of real beer. While they were unable to arrest anyone, they felt like they had a small victory, and a strategy to get a Capone’s operations.

Ness had a ten ton truck outfitted with a heavy steel bumper in case they came upon another set of steel doors they would be able to bust them down. Another wildcat brewery was identified on South Cicero Avenue. This time, using the truck as a battering ram, they busted through the front doors, and then a false wall, several fermentation vats and five men working, including Steve Svoboda, a master brewer for Capone’s organization.

It was during this time that the issues between Bugs Moran and Capone came back to life. Moran wasn’t living up to his end of the bargain that had been worked out at the peace summit in 1926. Moran and Capone had never really buried the hatchet, and in late 1928 and early 1929, Moran had cut some deals to have hijackers grab Capone’s whisky shipments coming in from Canada. Capone learned through an associate of Moran’s what was going on.

Al Capone and Bugs Moran

On February 13, 1929, Moran received a phone call from a hijacker saying that he had just brought in a truckload of Canadian whisky from Detroit and Moran could have it for a really good price. Moran didn’t ask questions, greedy to get a good deal on the hooch right under Capone’s nose. It was agreed that the whisky would be deliveredthe next morning at 10:30am to the garage of SMC Cartage Company, a warehouse that Moran used to move product.

At 10:30am on February 14th, St. Valentines Day, four men arrived at SMC Cartage Company garage, two of the men in police uniforms and two in plain clothes, where they found seven men, whom they lined up along the wall, and then the men in plain clothes with long top coats, pulled out Thompson Submachine guns and opened fire.

When the real police arrived they found all but one of the seven men dead, and he refused to say who had done the shooting, and he died three hours later. Among the dead was Moran’s second in command of the gang, a bookkeeper, an associate member who ran a number of laundries shops for Moran, two of the gang’s enforcers, another associate who handled Moran’s gambling operation, and the garage’s mechanic.

Carnage of the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre

But, they missed Moran. He decided to sleep in, letting his number two handle the whiskey transaction, which turned out, of course, to be a ruse to get as many of the gang’s members together in one place as possible. Eyewitnesses didn’t call the authorities right away, because when the looked toward the garage after the shooting they saw two police officers, guns in their hands, leading to men in topcoats and hats, hands in the air, to a car, which they entered and then drove away.

It was later learned that Capone had rented a house across the street from the location, and it was occupied by lookouts on the day of the massacre. Bugs Moran, furious and scared, immediately told the police and the feds that the St Valentine’s Day Massacre had to have been the work of Capone. A summons to appear before a grand jury on the incident was issued to Capone, but he feigned illness as an excuse not to appear. On March 27, when he appeared in court to testify on his own behalf in an unrelated prohibition case, FBI agents arrested Capone for contempt of court in connection with not appearing before the grand jury. He posted bail, and went on his way. In time, all charges against Capone related to the Massacre were dismissed.

In the meanwhile, Ness continued to bust brewery after brewery, using the same tactics; follow the empty barrels and eventually they’ll take you to the beer. Equipment was seized, workmen arrested, including Svoboda a second time and another Capone brewer, Bert Delaney. Ness had wire taps on the phones of all possible associates to Capone and the illicit breweries, and they were soon able to identify the locations of many operations and bust them; wildcat breweries were found at the Old Reliable Trucking Company on South Wabash, an abandoned warehouse on North Kilbourn Street, and another location on South Wabash, which they had learned of through tapping a phone conversation between Capone’s brother Ralph and an associate- it would turn out to be the biggest raid of all. On June 12, 1930, Ness’s brother in law, Alexander Jamie raided the South Wabash location and seized 50,000 gallons of beer, one hundred and fifty thousand gallons of fermenting mash, two brand new trucks, and six men arrested. In his book The Untouchables, published in 1957, Ness took all of the credit for the Wabash Raid, as it came to be known, although he was never there, and he never mentions Alexander Jamie anywhere in the narrative.

This wasn’t Nesses only time to be braggadocios about his exploits, or lack there of; he claimed in his book that he had raided 25 breweries and seized 45 delivery trucks, however US Attorney’s records from the time state otherwise, documenting only six breweries raided, along with five large beer distributing warehouses, with only 25 trucks and two cars were seized.

Also in his book, Ness describes a parade he organized to infuriate Capone. Supposedly, Ness assembled a number of vehicles that had been seized from Capone’s breweries, including pickups, ten ton freight trucks, and glass lined tank trucks, and he had his agents drive them down Michigan Avenue where they stopped in front of the Lexington Hotel, Capone’s headquarters. A phone call was placed telling Capone to look out his window at exactly 11:00am. According to Ness, who heard from an informant, Capone was infuriated, saying “I’ll Kill ‘im, Ill Kill ‘im with my own bare hands!” However, no other source can verify the event, which leads many to believe that Ness made up the entire incident.

The culmination of all of Ness’ and his men’s investigations finally came to fruition on June 5, 1931 when Al Capone was indicted by the US Attorney on charges of Tax Evasion. A week later another indictment was filed against Capone for violations of the Volstead Act. Capone was charged with more than 5,000 offenses against the United States in regards to Prohibition, but the US Attorney was convinced he had a better case with the tax charges, and proceeded. Presenting as evidence his lavish lifestyle, and the connection could be made between many purchases made by Capone, it was estimated that the gangster owed the United States at least $215,000 dollars in taxes. He was convicted in November of 1931 of Tax Evasion, and sentenced to eleven years in federal prison.

After being held in Cook County Jail he was transported to the Federal Penitentiary in Atlanta. In 1936, suffering from the effects of long term syphilis and gonorrhea, Capone was transferred to the newly opened Alcatraz penitentiary, where he spent most of his term in the prison infirmary. A shell of a human being at this point, he paroled in 1939, and referred to Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore to receive treatment for late stage syphilis, but Johns Hopkins refused to accept him, but Union Memorial Hospital did. Grateful for the care he received, Capone donated to Japanese Cherry Trees to Union Memorial. In March of 1940, Capone left Baltimore for his mansion at Palm Island, Florida.

It is said at the end he had the mental acuity of a 12 year old. On January 22, 1947, Capone suffered a stroke, three days later he died, surrounded by his family and Mae, his loyal wife of 29 years. He was buried in Mount Carmel Cemetery, the same resting place as Dion O’Banion and Hymie Weiss.

A few months after the Capone conviction in 1931, in the mayoral election of 1932, William Big Bill Thompson, without the backing of Capone’s dollars, was defeated by Anton Cermak. Cermak, a known advocate of repeal, ran on the platform, as did many politicians nationally, including presidential candidate Franklin Delano Roosevelt in 1932. Coming to office on March 4, 1933, on March 22 FDR signed Cullen Harrison Act, legalizing beer manufacturing of beer of 3.2% alcohol and wine of the same alcohol content. On December 5, 1933, the Twenty First Amendment of the United States Constitution was ratified, repealing the 18th Amendment, and so the failed experiment of Prohibition ended nationally in the United States.

Eighteen individual states, however, still had Prohibition laws in place, which kept moonshiners and bootleggers in business for many years to come. The last state to repeal prohibition was Mississippi in 1966, although there are still many counties and municipalities in the South where even today you can’t buy a drink, a bottle, or six pack.

After Prohibition, Eliot Ness was assigned to Ohio, where he went chasing down moonshiners in southern Ohio, Kentucky and Tennessee. In 1935 he left the Treasury department and went to work for the city of Cleveland as Safety Director. He vowed to root out corruption in the police and fire departments of that city. He divorced in 1938, and that same year he went after the mafia in Cleveland, but his career gradually withered. In 1942, he and his second wife moved to Washington DC where he went to work for the Federal government trying to clean up prostitution around military bases, where venereal disease was a major problem. In 1944 he went to work for a security safe company in Ohio. He ran unsuccessfully for mayor of Cleveland, was fired from his security safe job in 1951. Divorced a second time, and married a third, he bummed from this job to that, heavy drinking seemed to be the reason he couldn’t hold on to employment- the irony being that the biggest crusader against bootlegging in Chicago during Prohibition turned out to be an alcoholic. He fell in with a writer who helped him compose his book, The Untouchables in 1957, just before he died, a broken and forgotten man. The Chicago newspapers carried no obituary notices, and it wasn’t until his book was adapted into a television series in 1959 that Ness gained national attention.

Ness claimed that Capone offered him $1,000 a week if he would have just looked the other way during his investigations, but Ness said he refused. Of course, there’s no evidence that Capone ever made that offer other than Ness’s word. Some historians don’t believe that Capone ever met Ness, and that the gangster wouldn’t have known him from the proverbial Adam if they passed on the street. All Ness was to Capone was another G-Man trying to take him down.

Some last thoughts about Al Capone. One biographer talked about how much he was beloved in the Italian American neighborhoods of Chicago. When the great depression hit in 1929, Capone gave men jobs, he’d rent garages and basements and spare rooms from people for $25 to $75 a month, and never used the properties. He’d have groceries delivered to widows, and started a program to make sure that all of the school children in Chicago had milk everyday. Now this may have been self-serving, as the Capone organization had bought several dairies in the Chicago area, which they were using to launder money. He also instigated a system of expiration dates being put on the caps of milk jugs because a child of a family he knew had died from drinking bad milk. He lobbied to have it made a law that all milk in Chicago had to be dated. Of course he had the machines to put the expiration dates on the milk caps. Again, it may have all been self-serving. But his death was grieved by and his funeral was widely attended by the Italian Americans of Chicago, and to this day, flowers are still regularly placed upon his grave.

Works Cited:

“Al Capone.” FBI: History. https://www.fbi.gov/history/famous-cases/al-capone

Bergreen, Lawrence. Capone: The Man and the Era. Simon & Schuster, New York. 1994

Encyclopedia of Chicago History Online. 2005. http://www.encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org/

Perry, Douglas. Eliot Ness: The Rise and Fall of an American Hero. Penguin, New York. 2014.

“Sieben’s History.” Sieben’s Brewing. 2006. http://www.siebensbrewing.com/history.htm

Skilnik, Bob. Beer: A History of Brewing in Chicago. Barricade Books, Fort Lee, NJ. 2006

The Lifeblood of a Small Nation

In the far northeast end of Ireland, from County Antrim, if you look out just 12 miles across the North Channel of the Irish Sea, you will see the Scottish headland known as the Mull of Kintyre. On a clear day the misty craggy cliffs of the Mull can be seen rising, almost beckoning one to cross the water. I know. I’ve been there. I’ve looked out across the channel and wanted cross over to Scotland, but, I have yet to go there.

I’m not the first to long for that crossing. Even before the channel was covered in water, there was a land bridge; archaeologists tell us that the first human beings, hunter-gatherers to arrive in Ireland crossed over on foot near the end of the last ice age, around 10,000 BCE. When the Celts arrived in Ireland in the 6th Century BCE, they called the original inhabitants the Fir Bolg, sometimes called the ‘Dark Men.’ It is believed that the Fir Bolg assimilated with the Celts, probably not of their own volition but through violence and subjugation, and their legends and culture were adopted and morphed into the Celtic mythology. According to legend, the Túatha Dé Danann, translated to ‘the people of the gods,’ came from the North, presumably crossing over from Scotland, and gave the Fir Bolg a home in Ireland. The connection between Ireland and Scotland from the beginning of history has, literally, been legendary.

In the 5th Century CE, an Irish tribe of Celts called the Dál Riata, crossed the North Channel from Antrim and expanded their territory into the Mull of Kintyre and the Argyll regions of Scotland. Before the Dál Riata arrived in Caledonia (what the Romans called the land that would one day be called Scotland), according to Roman historians in Britannia, the only people living there were the Picts, another group of Celtic tribes that had migrated into Scotland from England. The Picts were so troublesome for the Romans that they built two walls, Hadrian’s Wall in the 120’s CE and the Antonine Wall in the 140’s CE in an attempt to keep the Picts out. But the Roman army left Britannia in the 400’s, leaving a power vacuum; the Picts expanded into northern England, the Angles and Saxons invaded Essex and East Anglia, and the Dál Riata expanded into western Scotland. Within 100 years the Dál Riata held three times more territory in the west of Scotland as they did in the north of Ireland.

The exchange of culture and trade across the North Channel between Ireland and Scotland was solidified for the next Millennia, interrupted only briefly by the Viking invasions of the 8th and 9th Centuries. Clans like the MacFergus (i.e. Ferguson), MacDonald, McConnell, McKay, Campbell, Kerr, MacGovern, MacAdoo, Murdock, MacAlpin, MacAngus, MacConnahey, Costigan, among others, intermarried, fought together and against each other, some had land holdings in both Ireland and Scotland. They shared the same early Christian beliefs, most of which had been spread through the establishment of monasteries by Irish St. Columba of Donegal. They traded goods and ideas. One of which was whiskey.

Lands held by Dál Riata circa 5th - 6th Century CE

It was Christianity that brought whisky to Europe. Irish monks in the mid First Millennia AD, about the same time as the Dál Riata were expanding into Scotland, these monks brought the art of distillation to Ireland from the Near East. Alembic stills were brought to the monasteries of Ireland and Scotland and used for distilling medicinal and aromatic therapies. At some point in time, some of the monks had the brilliant idea of distilling ale, which separated the alcohol in the ale from water, that is the ‘Spirit’ of the drink. The monks called these earliest distilled spirits Aqua Vitae, Latin for “The Water of Life,” but in the local vernacular, the Gaelic language, ‘Water of Life’ translated to Uisce Beatha, which over time was shortened to Uisce, and later was Anglicized by the English speakers to “Whisky.”

Now whisky, whether it is from Ireland and spelled Whiskey, or from Scotland and spelled Whisky, was in the Medieval period regardless of where it was made, basically the same thing; water, malted barley, yeast to make the mash, and then it would be distilled. This art of distilling seems to have spread through both Ireland and Scotland around the same period, which would make sense, since the monks of various monasteries across the region would have shared recipes and techniques regarding whisky production. The two earliest written references we have of whisky being made are both from the 15th Century, and one is from Ireland and the other was from Scotland. In Ireland, in The Annals of Clonmacnoise, it was described how a head of one of the clans died at the monastery after drinking an excessive amount of aqua vitae. In Scotland, King James IV granted a large amount of malt to one Friar John Cor specifically for the making of aqua vitae for the Scottish court. And while this is the first written word regarding whisky production in Scotland, undoubtedly the spirit had been being distilled for many decades, if not centuries, prior to the written documentation, since we know that the monks had knowledge of distillation going back a thousand years earlier. My guess is that they had been distilling ale for a long time, they just hadn’t let the word out to the rest of the world. Maybe they wanted to keep it all to themselves.

In the medieval period there were no laws in Scotland regarding exactly how spirits had to be produced to be called whisky. But, today, according to the Scottish Whisky Regulations of 2009, whisky in Scotland must meet certain requirements to be called Scotch. It has to be produced from a licensed distillery in Scotland, and that includes mashed, washed, fermented, and distilled on the grounds of the named distillery. The spirit must be twice distilled. It must be fully matured in a licensed warehouse in Scotland in Oak casks of no larger than 700 litres volume (that is 185 US Gallons) for a minimum of 3 years and 1 day. It may contain no other ingredients except water and plain unflavored caramel coloring (though only the cheapest of blended whiskies would ever add coloring), and it cannot be less than 40% Alcohol by volume (that is, 80 proof).

There are really only two types of Scotch whiskies, but these two types are used to make four varieties. The most well known type is Single Malt Scotch. Single malt must be produced from a single distillery using only water and malted barley by batch distillation in single pot copper stills. The other type of whisky is Single Grain Scotch, which is also produced at a single distillery, but along with water and malted barley, it may include grain whisky made from another type of unmalted grain (that is corn, or rye, or wheat) or perhaps malt from one of these grains. The word single in either of these types denotes that came it came from a single distillery, not a single type of grain. Now, from Single Malt and Single Grain whiskies, the four varieties of whisky are made: Of course, Single Malt Scotch. Then it gets confusing to the layman, so follow me here.

There is Blended Malt Scotch Whisky, which is a blend of two of more Single Malt whiskies from two or more different distilleries. Then there is Blended Grain Scotch Whisky, which is a blend of two of more single grain whiskies from two or more different distilleries. And then there is Blended Scotch Whisky which is a blend of one or more single malt Scotch whiskies with one or more single grain Scotch whiskies. Blended Scotch accounts for 90% of the whisky produced in Scotland; all the well known brands, Dewer’s, Johnny Walker, J&B, Cutty Sark, Famous Grouse, Chivas Regal, Bells, Ballentine’s, Grant’s, Teacher’s, and so forth.

Now besides types and varieties of Scotch, there are five regional areas of Scotch distilling.

Lowland Scotch comes from southern Scotland, basically the area south of a line drawn from Glasgow to Edinburgh to the English border. There are currently only five distilleries in the Lowland region.

The Speyside has the most distilleries, 103 is the most recent account. Speyside gets its name from the River Spey that flows through the region west of Inverness and the area is centered around the town of Elgin. It is said that the water from the Spey is exceptionally well suited to Scotch distilling, and some of Scotland’s most famous Single Malts hail from this region, including Balvenie, Cardhu, Glenfiddich, The Glenlivet, and The Macallan.

The Highlands are the largest region by far, and include the sub region that includes the islands of Skye, the Hebrides, and Orkneys. Famous Highland Distilleries include Dalmore, Glendronach, Oban, Glenmorangie, Highland Park, and Taliskar.

Campbelltown is the smallest region, which is centered around the community of the same name on the Mull of Kintyre. At one time there were 34 distilleries in the area, now there are only three; Glen Scotia, Glengyle, and Spring Bank.

The last area, Islay, an island just west of the Mull of Kintyre and north of Ireland, is probably best known for the smokiness of the malt whiskies they produce. My favorites from this region are Caol Ila, Lagavulin, and Laphroaig.

Whisky Distilling Regions of Scotland

All of the regions produce somewhat different styles of Scotch; Lowland whiskies tend to be soft and light, with grassy notes with subtle tastes and delicate aromas. Speyside whiskies are known for sweet fruity character. Highland whiskies go from very dry to sweet; lots of variations, just like the landscape of the Highlands itself. Islay whiskies are dry, salty, and very smoky.

Since all whiskies, wherever they are made, are basically the same ingredients; malted and unmalted grain, water and yeast, what makes Scotch… Scotch? Three things make Scotch unique, or which Scotch shares 2 with most other whiskies; First, there is Copper pot stills, which are built in such a manner that as the vapors rise those that are not as light condense at the top of the still and drop back into the wash to be distilled again. Secondly, cooperage and the aging of the whisky in Oak barrels, most of which have been previously used in the aging of American Bourbon, Sherry, Port, Madiera, or Bordeaux and then recharred to bring out the hidden flavors in the wood. Irish whiskey distillers use previously used barrels, however most American whiskey and bourbon distillers use new charred barrels.

Copper Pot Stills at The Glenmorangie Distillery, Ross-shire, The Highlands

But the thing that makes Scotch unique is how the malt is dried over an open peat fire. Peat is partially decayed vegetation or organic matter that is unique to natural areas called bogs, which are found all over Scotland. Peat is harvested by cutting it from the ground and then allowed to dry after which it can be burned. It was an important fuel source for many populations for thousands of years, including the Scots and Irish back during the formative years of whisky development. Malted barley is barley that has been steeped in warm water, begins to germinate, which converts the starch in the grains into sugar, then the germination is stopped by drying the barley with heat. Malt for Scotch is dried, in varying degrees depending upon the distillery, over an open peat fire, with the peat imparting smoky flavoring to the malt, again in varying degrees. The malts of other whiskies are generally dried in a closed kiln so the smoke from whatever the fuel may be does not reach the grain. The flavor of peat smoke is the one thing more than anything else that gives Scotch its unique taste and character.

Peat being harvested from a blanket bog on the Isle of Skye, Scotland

From the 1400’s onward, whisky was the favored drink in Scotland, and was an intrinsic part of Scottish life, particularly among the Lairds and Landowners, who had their associated monasteries, which they sponsored, make whisky for them. But during the Scottish Reformation of the mid 16th Century, a tumultuous period when the Catholic Church and the Protestant Calvinists vied for control over the Scottish Throne, Catholic monasteries, where whisky was made, began to lose many monks, priests, and friars, who in fear of repercussions if the Calvinist proved victorious, left Scotland for the continent. By 1570, during the regency of James VI, who was controlled by the Calvinists, Catholic monasteries across the kingdom, ceased to exist.

The friars and monks, who had previously distilled whisky for the church, then began to work for the wealthy lords and landowners, many acting as personal clergyman in hiding, within the realms, taking whisky making to the public. The tenants and workers on these estates learned the art of distillation from the monks and then began practicing it themselves. In 1644 the Scottish Parliament imposed a tax on all distilled spirits. The Scots distillers took their profession into hiding, practicing the craft far up into the mountains, and often did their work at night. This illegal spirit that they concocted began to be called by a couple of now quite famous nicknames; mountain dew and moonshine.

To send the craft of whisky distillation further underground, in 1707 when the Act of Union united the English and Scottish crown, Parliament in London imposed an additional tax on malt purchased by the distillers. The lords of Scotland who had operations took them into remote areas, and assembled their own private guards and armies to protect their distilleries from the royal excise tax collectors, and a wide spread black market for whisky developed.

In 1823, under the leadership of the 4th Duke of Gordon, the Excise Tax of 1823 was passed, which allowed for distillers to produce their product legally under a license. The producers would also have to pay a small percentage of tax based upon gallons sold, and the malt tax would be done away with. Gordon encouraged a tenant of his, George Smith, who was well known in the area for producing some of the finest single malt whisky, to come out of hiding and begin producing his whisky legally. Gordon even offered to help Smith with the licensing fee. Gordon was prompted into this action, according to legend, when his estate was visited by King George IV. Gordon proudly offered his royal guest a dram of the locally produced whisky. The king loved it. He wanted to meet the distiller and to purchase a large quantity for himself to take back to London. Of course, Gordon knew this was impossible, since George Smith as a moonshiner, but he was able to put his majesty off, he made an excuse, nobody is sure what exactly, but he promised his highness that he would procure some of the elixir for him soon and deliver it personally to the royal court. The name of that whisky; The Glenlivet, still one of the most popular Single Malt whiskies in the world.

The Glenlivet Distillery, Speyside, near the village of Ballindalloch

In 1824 George Smith became the first distiller in Speyside to apply for a license under the king and produce whisky. Smith was threatened with violence by other illicit distillers who wanted the Excise Tax to be repealed and they knew as long as some distillers accepted it, it would continue to be inforced. Gordon gave Smith his full backing and protection, and symbolically gave him a brace of pistols for his own protection and the protection of the distillery. The Glenlivet grew, with the help of high society in London, and by 1849 a second distillery was built. It too was soon running at capacity, and a third distillery was built in 1858. Unfortunately the second distillery was lost to a fire while the third was under construction. But, by leading by example, George Smith, and The Duke of Gordon, and The Glenlivet, brought Scotch whisky out of the mountains and back into the legal light of day.

The next big thing to happen to Scotch was the invention of the continuous still by Aeneas Coffey and the production of Grain whisky, beginning in 1831. Grain whisky was lighter than the more robust, intense malt whiskies, and with the melding of the two whiskies into Blended Scotch, and thus a spirit was produced that appealed to a much larger market segment.

Coffey’s Continuous Still Diagram, used in the making of Grain whiskey

Traditional Copper Pot Still Diagram

In 1880 another fortuitous event accidently helped promote Scotch in the eyes of the world. The preferred cocktail among elite society and the emerging middle class in both Europe and America was brandy and the recently invented carbonated soda. At the time most brandy was made in France, but along came the Phyloexera beetle, that attacked grape vines and within a few short years the vineyards of France were devastated to the point that wine and brandy virtually disappeared from the market. In it’s place consumers turned to whiskies, both Scotch and Irish, to mix with their soda. By the early 20th Century, whisky and soda, or Scotch and soda, was the most popular cocktail in the world.

Scotch continued to have some additional good luck, much of it at the expense of the Irish whiskey producers. At the beginning of World War I, Jameson Irish Whiskey is thought to have been the most popular whiskey in the British Empire. But, in 1916 the first salvo of the Anglo Irish War between the Irish Republican movement that lasted until peace was obtained in 1922 with the formation of the Irish Free State. During the war in Ireland, barley production was severely short, and whiskey production in Ireland fell dramatically.

Then in 1920, American Prohibition was enacted. According to legend, American Gangster named Jack “Legs” Diamond first approached Old Bushmills distillery and then the Jameson Distillery in Ireland. He wanted to make a deal, but for whatever reason, a deal couldn’t be worked out with the Irish distillers. Diamond then went to London and walked into Berry Brothers & Rudd on St. James Street, the largest wholesaler of spirits and wine in Britain, and ordered several hundred cases of their best Scotch. The spirit purveyors did not bat an eye.